Is This a Whip Which I See Before Me?

For

dedicated GMT customers, the setting will be familiar: ancient Rome, with all

that that implies. However, once the box lid comes off, the game found inside

is not an elaborate wargame with the usual bells and whistles, but rather a

thrilling chariot racing game—clever enough to please elements from the

hardcore crowd, yet simple enough to bring casual players along for the

eventful ride.

(As far as I can tell, this is the fifth racing game published by GMT, after Formula Motor Racing (1995), Thunder Alley (2014), Grand Prix (2016), and Apocalypse Road (2020). One could even argue in favor of a sixth entry, if you decide to count the chariot racing mini-game found in Reiner Knizia’s Rome triptych, from 2001. Impressive for a wargaming outfit!)

On a long and narrow oval of a dirt track, two to six players attempt to drive their chariots through the traffic and mayhem, in the hopes of crossing the finish line before anyone else at the conclusion of three laps.

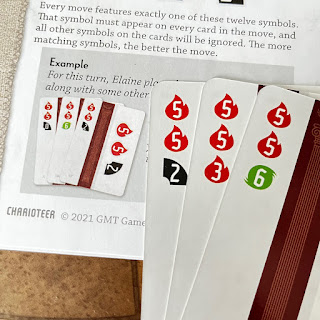

Movement

is achieved by playing sets of cards with matching symbols, which in this case

means matching numbers in the same color. For instance, a bunch of red 3s, or

yellow 4s, or green 6s. (All other colored symbols on the cards are ignored.)

|

| Three valid hands |

In

the middle of the board sits the Crowd Card, available to any player who

matches it with at least one card from their hand. (Think of it as a community

card in Texas hold ‘em poker.) Players are allowed to play up to three cards,

plus the Crowd Card as a potential fourth.

Each

player’s chariot movement is then tallied by adding the number of matching symbols

on the played cards, plus the actual number inside those matching symbols. So

four red 5s (4+5) would add up to a movement of 9.

Since

each player holds a hand of eight cards and

can see future Crowd Cards two turns in advance, the game quickly becomes a

hand-management challenge.

But

what about the racing itself?

The

track is made up of a series of wide spaces—each able to accommodate any number

of chariots—laid out in a straight line. Yes, the track includes two curved

ends so the chariots can double back, but it remains a single-space-wide

succession of steps. In other words, positioning is not an issue and each move

is a question of distance, with no maneuvering involved. Which makes sense:

chariot racers evolved in spaces so vast that—apart from how you approached the

next corner—they didn’t have to worry much about blocked lanes.

And

this is where things get very interesting.

Each

space contains a potentially infinite series of spaces, much like a fractal. If

a chariot reaches a space already occupied by another, it’s placed to its

right; it must then spend a movement point to pass that chariot (by moving to

its left), before it can leave that space and keep moving forward.

So

if my chariot is the fourth one to land on a space, I’ll need to spend three movement

points to pass each of my competitors before I am allowed to surge ahead once

more.

|

| Yellow has a lot of work to do. |

Corners

are also handled in a clever way: a black move (which incidentally features the

lowest possible numbers in the game) allows a chariot to round a corner using

the inner (pale) spaces, whereas a move in any other color forces the chariot to

also count the outer (dark) spaces,

in a zigzag move that makes the corner much longer to clear. (And yes, chariots

still pass one another using the mechanism highlighted above, no matter the

color of the space on which the jockeying happens to take place.)

|

| Blue and Gray taking the long way around |

So

what special effects do the other colors trigger?

Red

represents an abstracted “attack” on all other chariots—think of it as debris

on the track, horses getting spooked, maybe a spoke breaking on a wheel or two…

A three-card red move inflicts one damage on all competitors, while a four-card

red move inflicts two points of damage. Until gotten rid of, damage is

subtracted from each move an afflicted chariot makes.

Yellow

repairs/heals/shrugs off damage, by removing half of the damage (round up) from

your chariot.

Green

doesn’t grant any special capabilities, but it features the highest numbers in

the game—up to a whopping 6! After playing a big hand of yellow 0s to get rid

of some damage, you’ll appreciate how fast green can get you to the next

corner.

A

hand of six or more matching symbols grants its player a random, colored token,

which is added to the five everyone starts the game with. Played alongside a

matching hand of cards (red on red, yellow on yellow, etc.) they grant their

chariot an additional ability: move faster, avoid any damage this turn, heal

half of your damage, or change the color of an odd card! Similar symbols also

appear on cards, next to colored symbols: use them well.

|

| A smattering of tokens |

Each move grants one experience point in that color, advancing the relevant cylinder forward one step on that player’s board. (If the Emperor’s die, rolled each turn, matches the color you decide to play, you get two experience points!) While in the central zone, each cylinder grant a +1 move bonus in the corresponding color; and when a cylinder reaches the end zone, it is locked in place for a juicier move bonus, albeit one that will most likely be of service just once more before the race is over.

Experience

is hard-won.

RULES

OF ENGAGEMENT

Charioteer comes to life

with only 10 pages of rules, which shouldn’t scare away modern eurogamers. The

game can be taught in about 10 minutes, with very few exceptions or

out-of-character wrinkles.

That

being said, for a relatively simple game aimed at the general public, the

rulebook commits some explanatory faux pas—from illustrated examples that don’t

resolve the one question newcomers are most likely to ask (“Can I count my red

3 amongst all the red 5s?”) to a missing turn sequence that would have shed

some welcome light on the exact timing of actions.

|

| Original example & what I think would have helped |

The

worst offender in this regard concerns the experience track. Cylinders that

start on the lower spaces of a player board (per a randomly assigned skill

card) must first climb to the top before they can start moving laterally and

produce their +1 bonus.

Yet this isn’t stated anywhere in the rules: you have to deduce the procedure

from a line about some skills being more advanced than others at the start of

the race, together with the subtle visual hint on your player board.

|

| Moving up before moving right |

Now,

although unfortunate, none of those issues would harm a wargame, whose target

audience almost enjoys looking up answers and clarifications online (it’s how

we interact socially). But it’s a sin for a game with mass-market appeal and

where, if you convince casual gamers to put aside their fear of that red,

square logo—I’ve heard this many times—you must then explain the game in a way

that is perfectly clear, so as to prove to them that they were right to trust

you. And that the red logo doesn’t bite.

As

I said with Apocalypse Road two years

ago, my hope is that non-wargamers will grab the box off the shelf, admire its

stunning cover image, then get into the action and realize they really should look

into GMT games more often.

FUN

FACTOR

Novel movement mechanics and clever hand management will only take you so far: is the game any fun? You bet your horse’s ass, it is. Charioteer can be all at once fast, exhilarating, frustrating, headache-inducing… Everything you want in a racing game.

The Crowd Card will throw a wrench in your decision-making process: should I take advantage of it (and possibly score a bonus token), or should I stick to my plan to play a black move going into the next corner? The fact that future Crowd Cards are revealed two turns in advance allows you to plan accordingly—of fume over your bad hand when the planets stubbornly refuse to align.

I’ve found the Emperor’s die to be the most disruptive element of all. Since it grants an additional experience point whenever you play the color asked for, it’s oftentimes really hard not to acquiesce, despite your best intentions.

The absence of direct player attacks will no doubt irk some gamers out there, but not everything is a wargame! And the red-moves-damage-everyone proposition creates tense situations where you need to keep on your toes even when no other chariot is physically near yours. Especially when the Crowd Card is a red one, or when the Emperor rolls red on his die. And if the two should occur at the same time, you better hope you’re in a position to play one of those cards with a shield icon (or else a shield token) to block all damage for the turn.

Player

count plays a big part in the fun that Charioteer

can generate. The game is rated for 2-6 players, but with just two or three

chariots kicking up dust around the track, a lot of the excitement fades away. I

wish GMT had provided us with a bot system to make sure we always had a full

complement of chariots in every race—something that didn’t seem too daunting to

me, given that the track is essentially one long stretch of single-lane spaces.

Well,

it took me a bit longer than I anticipated (fine-tuning never ends!), but I

came up with a dice-based bot system that satisfies my needs, and might also do

the trick for you.

You

can find it here.

WAR

PRODUCTION

The big Charioteer box (which is quickly becoming the standard GMT box size) comes with two mounted boards that combine to create the extra long racing track. The boards look nice enough, but are missing that extra oomph you wish they had, so that passersby would stop and take a closer look. As one friend put it, “They do the job really well, but they’re very brown.”

The racing cards—a towering stack of ‘em—and the skill cards are cut from the thick cardstock we’ve come to expect from GMT, and I can attest to their resilience under heavy and repeated shuffling. (Those babies don’t need no sleeves.) The Emperor’s die is not engraved, but the color printing seems strong enough to survive many a racing season.

The

rest of the components are made out of wood, from the skill markers to the big

bag of bonus tokens, up to and including the chariots themselves! True,

plastics didn’t exist in ancient Rome.

PARTING

SHOTS

I love the puzzles players are tasked with solving throughout each race. How can I best use the hand I was dealt? Should I play two consecutive, mediocre hands, or just bite the bullet this turn and try to make a break for it next—assuming I draw the symbol I desperately need? The wheels never stop turning, both on the dirt track and between your ears.

A category of gamers will decry Charioteer’s simplicity (“What do you mean, no Combat Result Tables?!”) like it’s a bad thing. But I see it as a sort of thinking man’s party game, which is as close as you’ll get to a casual game while keeping things challenging and exciting. How many racing games can you teach in 10 minutes, and then go on to enjoy between 60 and 90 minutes of nail-biting decisions?

I initially questioned the inclusion of skill cards, used to determine the order in which each player’s skill markers begins the game. After all, you could just shake your four markers in your hands and put them down on your player board in a random order. (And who cares if two players happen upon the same combination, out of 24 possibilities.) But it’s exactly the kind of production move you make to grab the attention of more casual gamers: reduce friction, both before and during the game. It’s the same reason you go for wooden meeples and not cardboard counters, or for a board that’s super easy to read, perhaps at the expense of some visual pizzazz.

Now just give me an ironclad rulebook, and even the Emperor will have to bow down.

# #

#